Birth and the Book

Laurence Sterne himself was familiar with the medical members of the Good Humour Club and used their services and advice. In a letter sent to Theophilius Garancieres, a member of the Good Humour Club and apothecary of York, Sterne requests medications for his wife following a stillbirth. Further correspondence between Sterne and the apothecary suggest that the author trusted Garancieres’s judgment and used his medications on more than one occasion.

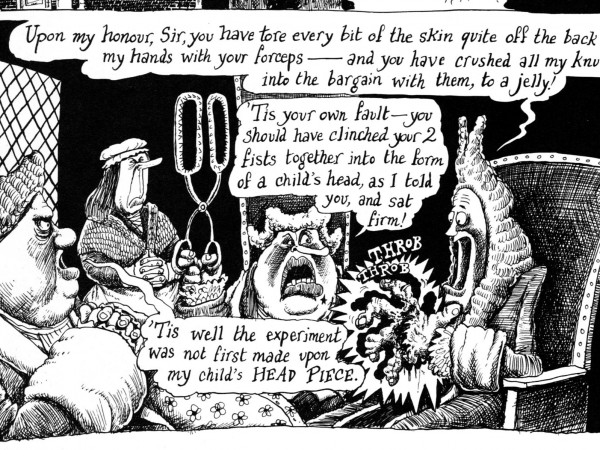

Although Sterne appears to have depended on Garancieres for advice following Elizabeth’s stillbirth (more happily, Mrs Sterne later gave birth to daughter Lydia, who survived into adulthood) he was also interested in other medical professionals who engaged with childbirth as a medical, scientific and life process. From medical men to midwives, Sterne explored changes in the way in which childbirth was dealt with in the community. This theme was used in Sterne’s The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, in a comic depiction of Tristram’s problematic birth, which was attended by both a midwife and an incompetent man-midwife, Dr. Slop. Although it is thought that Dr. Slop was intended to be a comic caricature of Sterne’s political opponent, Dr John Burton, who also offered his services as a practitioner to women in childbirth, Tristram Shandy also reflects a more serious curiosity towards the development of medical practice. Laurence Sterne expresses his own fascination with scientific innovation through his novel when first-person narrator Tristram explains to readers:

thus it is by the slow steps of casual interest, that our knowledge physical, metaphysical, physiological, polemical, nautical, mathematical, aenigmatical, technical, biographical, romantical, chemical and obstetrical, with fifty other branches of it (most of ‘em ending, as these do, in ical) have, for these last two centuries and more, gradually been creeping upwards.

As Sterne shows through his long list of discourses that had been developing, or ‘graually been creeping upwards’, although historically women were left to deal with the uncomfortable work of childbearing, obstetrics had been increasingly recognized as a science for the last 200 years before 1759, the year Sterne published the first volume of Tristram Shandy. Manuals on women’s health and childbirth had held a place in English bookselling since 1540, when a translation of a German medical manual Der Rosengarten was published in London. Translations of European texts were popular and frequently published from this point, with original books by English authors emerging from the mid seventeenth century onwards.

Thomas Graham’s medical book on diseases which affected women in the nineteenth century was first thought to have been published in 1834. It provides an example of how involved male practitioners had become with childbirth, both prior to and following the existence of The Good Humour Club. The pages shown explain how melancholic or ‘depressed states of mind’ can affect women after childbirth. Graham’s work points to what is now known as the ‘baby blues’ or, in some cases, postnatal depression. This can be a short or long-term condition and whilst there are many supportive measures which can be used to support new mothers should this occur today, Graham’s early remedy, similarly to Burton’s suggested herbal medication for melancholy, is black snakeroot.

Back to The Doctors’ Club