Humoral Medicine and Melancholy

Prior to the development of advanced medical techniques particularly in surgery, treatment for ill health was most commonly based on the theory of ‘humoral balance’. This was the idea that the human body relied on four substances that should be equally present in order to function properly.

The four humors were thought to be:

Blood

Black Bile (Melancholy)

Yellow Bile (Choler)

Phlegm

These issues of lifestyle advice became an increasingly important characteristic of medical guidance throughout the eighteenth century as melancholy, more readily known as ‘nerves’ or ‘spleen’ as the century progressed, became increasingly fashionable as a diagnosis, particularly with the upper classes. Following on from Burton, James Makittrick Adair, George Cheyne and John Armstrong were just a few practitioners who made these patient choices, regarding diet, exercise, sleep, residence and social interaction, their own area of medical expertise in an attempt to cure nervous conditions.

Up until the mid-nineteenth century medical practitioners believed that an imbalance, whether a deficiency or excess, of one or more of the humors led to illness or an altered temperament, or state of mind. The delicate balance of the humors was also thought to affect what was known as the ‘animal spirits’, the body’s communication to the brain through sensory and emotional responses. The absence of good humour was considered to have been caused by an imbalance of the bodily humors. Whilst later in the century, the management of melancholic conditions focused on routines of lifestyle, there were a large range of traditional methods available which, it was believed, would rectify the imbalance of humors. As it was thought that purging, or ridding the body of excesses found in the blood would cure a melancholic mind, treatments included blood-letting, applying leeches to the skin. On occasion, administering of medications were also thought to be helpful in cases of nervous disorders. Many of these substances, such as Robert Burton’s suggestion of Hellebore and Nicholas Culpeper’s contribution of Motherwort, were later found to cause potentially adverse effects or even poison the recipient!

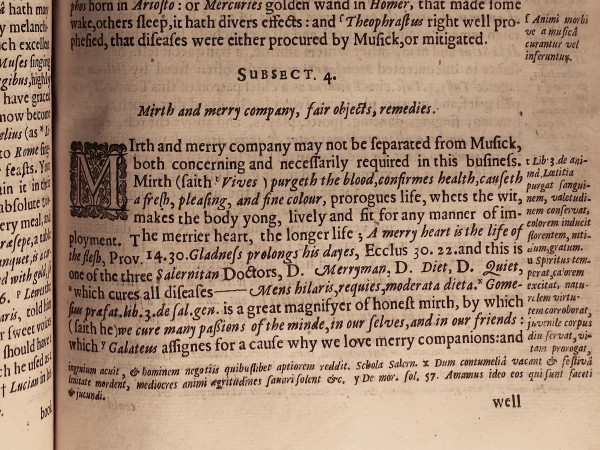

Robert Burton’s text The Anatomy of Melancholy was the first step towards producing a comprehensive study of melancholy, a diagnosis known today as depression. First published in 1621, the book is considered by many to be both a medical and literary classic and has been referenced by many authors since, including Laurence Sterne. These pages include Burton’s belief in the power of sociability on emotional health and wellbeing. His emphasis on ‘merry making’ is not dissimilar to the principles upon which The Good Humour Club was based. Burton summarized his own views in a comic description of the elements of a healthy lifestyle by referring to these elements as ‘Doctors, D. Merryman, D. Diet and D. Quiet – which cures all diseases’. Minute books of the Club which have been recovered so far prove that, whether or not they believed in ‘Quiet’, their activities point towards the remaining two elements. Their ‘merry making’ was typically accompanied by good food and drink in the form of ‘elegant supper[s]’ and ‘Crown Bowls of Punch’ contributed by members themselves or, on occasion, the Suntons – owners of the coffee house where the group met, with meetings later moving to the York Tavern.

Back to The Doctors’ Club